In ancient Greece, the great rival of Athens was Sparta. The city-state and its surrounding territory were located on the Peloponnesus, a peninsula southwest of Athens. Sparta (called Lacedaemon by themselves) was the capital of the district of Laconia. From the vigorous iron-hearted warriors of this city-state has come the English adjective “spartan” meaning “disciplined, extreme, self-denying, bold, brave”.

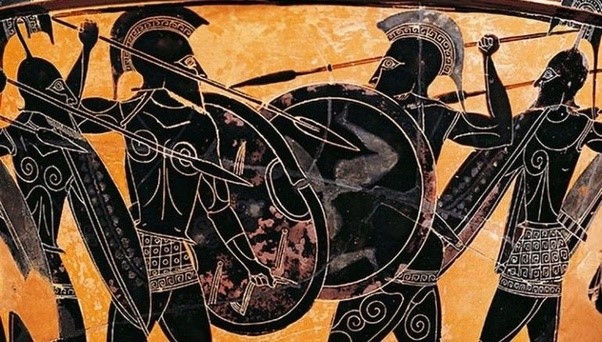

Sparta prided itself not on art, learning, or splendid buildings, but on its valiant men who “served their city in the place of walls of bricks”.

The Spartan government was founded on the principle that the life of every individual, from the moment of birth, belonged absolutely to the state. The elders of the city-state inspected the newborn infants and ordered the weak and unhealthy ones to be carried to a nearby chasm and left to die. By this practice Sparta hoped to ensure that only those who were physically fit would survive.

The children, who were allowed to live, were brought up under a severe discipline. At the age of 7, boys were removed from their parents’ control, placed in military barracks under the general charge of a state director of education, the Paidonomos, where they remained until aged 20.

Unlike the boys of Athens, they spent little time learning music and literature. Instead they were drilled each day in gymnastics and military exercises. They were taught that retreat or surrender in battle was disgraceful. They learned to endure pain and hardship without complaint and to obey orders absolutely and without question. The smallest offences were punishable by whipping, and food was deliberately rationed, so that the boys were forced to steal to get more. If they were caught they were whipped severely, not for the act of stealing, but for stealing carelessly and unskilfully.

Discipline grew even more rigorous when the boys reached manhood. All male Spartan citizens between the ages of 20 and 60 served in the army and, though allowed to marry, they had to belong to a men’s dining club and eat and sleep in the military barracks. They were forbidden to possess gold and silver, and their money consisted only of iron bars. War songs were their only music, and their literary education was slight. No luxury was allowed, even in the use of words. They spoke shortly and to the point–in the manner that has come to be called laconic, from Laconia, the district of which Sparta was a part.

There were three classes of inhabitants in Laconia. Spartan citizens, Spartiates, who lived in the city itself and who alone had a voice in the government, devoted their entire time to military training. The peroikoi, or “dwellers-round,” lived in the surrounding villages, were free but had no political rights. They were tradesmen, occupations that were forbidden to the Spartans. They were also called upon to fight in the Spartan army. The Helots were serfs, little better than slaves, bound to the farms and forced to cultivate the soil for the citizens who owned the land. These Helots, whose marriages and children were not so strictly controlled by the state, were the most numerous class and often bitterly hated their masters. Only the amazing organization and fighting powers of the Spartan state kept them under control.

Another strange feature of Sparta was its government, which was headed by two kings who ruled jointly. They served as high priests and as leaders in war. Each king acted as a check on the other. There was a sort of cabinet composed of five ephors, or overseers, who exercised a general guardianship over law and custom and in later times came to have greater power. The legislative power was vested in the assembly of Spartan citizens and in a senate, or council, of 30 elders consisting of the two kings and 28 other men chosen from the citizens who had passed the age of 60.

The Spartan constitution is said to have been founded by Lycurgus in the 9th century BC. Under the rigid discipline of its laws, Sparta extended its conquests over the neighbouring states until it gained control of most of the Peloponnese. Sparta’s prowess naturally brought rivalry with Athens, the leader of the northern states and for a time of all Greece. This rivalry culminated in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE), which resulted in Athens’ ruin and Sparta’s supremacy.

When it was necessary to fight, the effectiveness of the training was proved many times. The army was not beatxen in a strength fight from the period of the Messenian Wars (800 BCE) until the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE.

“In times of battles the officers relaxed the harshest aspects of their discipline and did not stop the men from beautifying their hair and their armour and their clothing, glad to see them like horses prancing and neighing before races. For this reason they took care over their hair from the time when they were youths, especially seeing to it in times of trouble so that it appeared sleek and well-combed, remembering a saying of Lykourgos about the care of hair, that it makes the handsome better-looking and the ugly more frightening. They also had less rigorous exercises, and they allowed the young men a regime in other respects less restricted and supervised, so that for them alone war was a rest from the preparation for war… It was an impressive and frightening sight to see them advancing in time to the flute and leaving no space in the battle-line, with no nervousness in their minds, but calmly and cheerfully moving into the dangerous battle to the sound of music.” – Herodotus

The ancient city of Sparta was destroyed by Visigoths in AD 396. The modern town, called New Sparta locally, was built in 1834 after the War of Greek Independence. It occupies part of the ancient site near the Eurotas River, about 15 miles (24 kilometres) from the Gulf of Messenia.