Ancient Greeks wrote their books on rolls of papyrus, but, as papyrus was expensive, they also wrote less important things on bits of pottery. They called these pieces of pottery ostraka (singular ostrakon, ὄστρακον).

These bits of ceramic gave their name to one of Athen’s more original political processes: Ostracism. Ostracism allowed the people to banish any prominent citizen from the city for 10 years, without bringing any charge against him. Each year, the Athenians were asked in the assembly whether they wished to hold an ostracism. If they voted “yes”, citizens wrote the names of the person they wanted to be ostracised onto pieces of pottery, and placed them into an urn. If at least 6000 votes were cast, then the person with the most votes “won”, and had to leave the city within 10 days.

Ostracism was designed to remove citizens who might threaten the stability of the state. But it was often used to get rid of politicians who had used up their good-will capital with the people. One of the most famous victims of ostracism was Aristides, son of Lysimachus, known as “Astrides the Just”. Aristides was an Athenian statesman in the early 5th century who played a key role in the Persian Wars. Herodotus calls him “the best and most honourable man in Athens”. Aristides disagreed with Themistocles regarding his naval policies, and this disagreement eventually became so violent that the Assembly voted to hold an ostracism, to banish one of the two politicians.

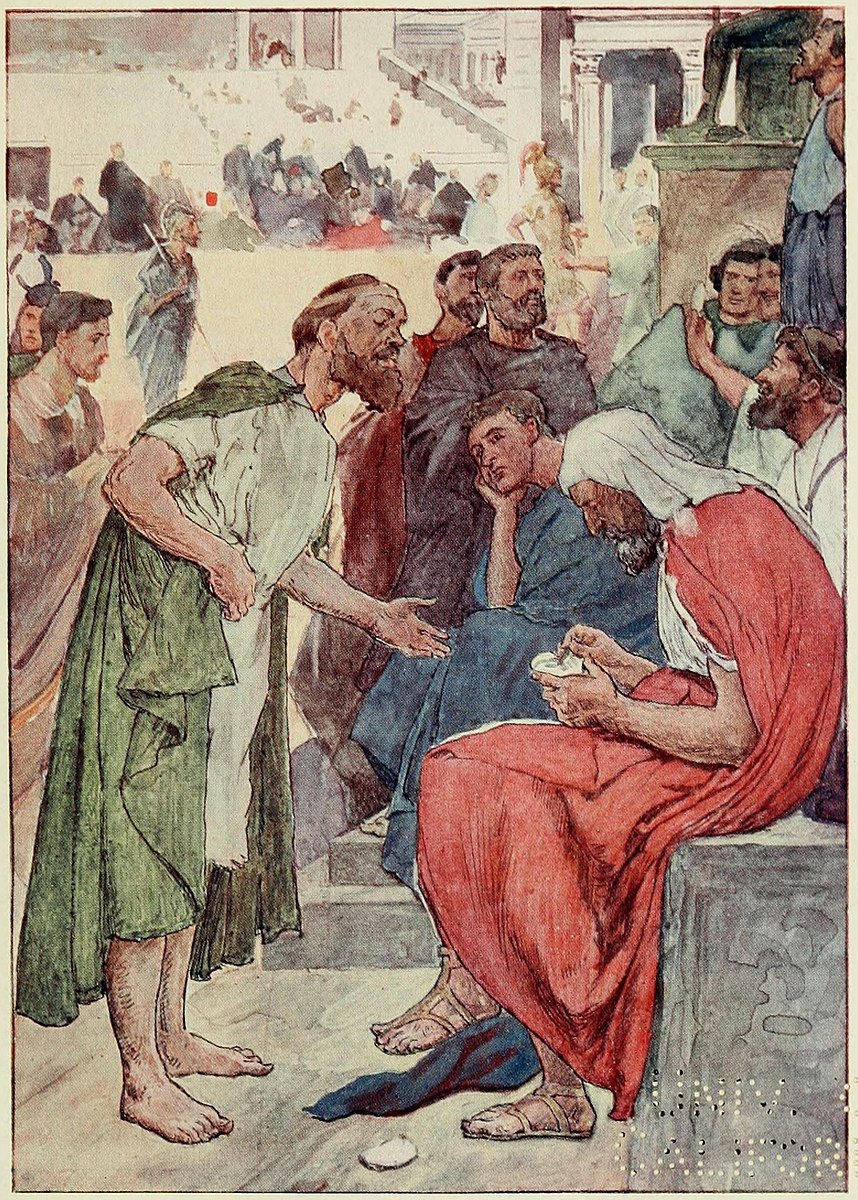

It is said that, on this occasion, an illiterate voter who did not recognise Aristides approached the statesman and requested that he write the name of Aristides on his voting shard to ostracize him. The latter asked if Aristides had wronged him. “No,” was the reply, “and I do not even know him, but it irritates me to hear him everywhere called ‘the Just’.”